DownEast of Eden

The remarkable oasis of Cobscook Shores

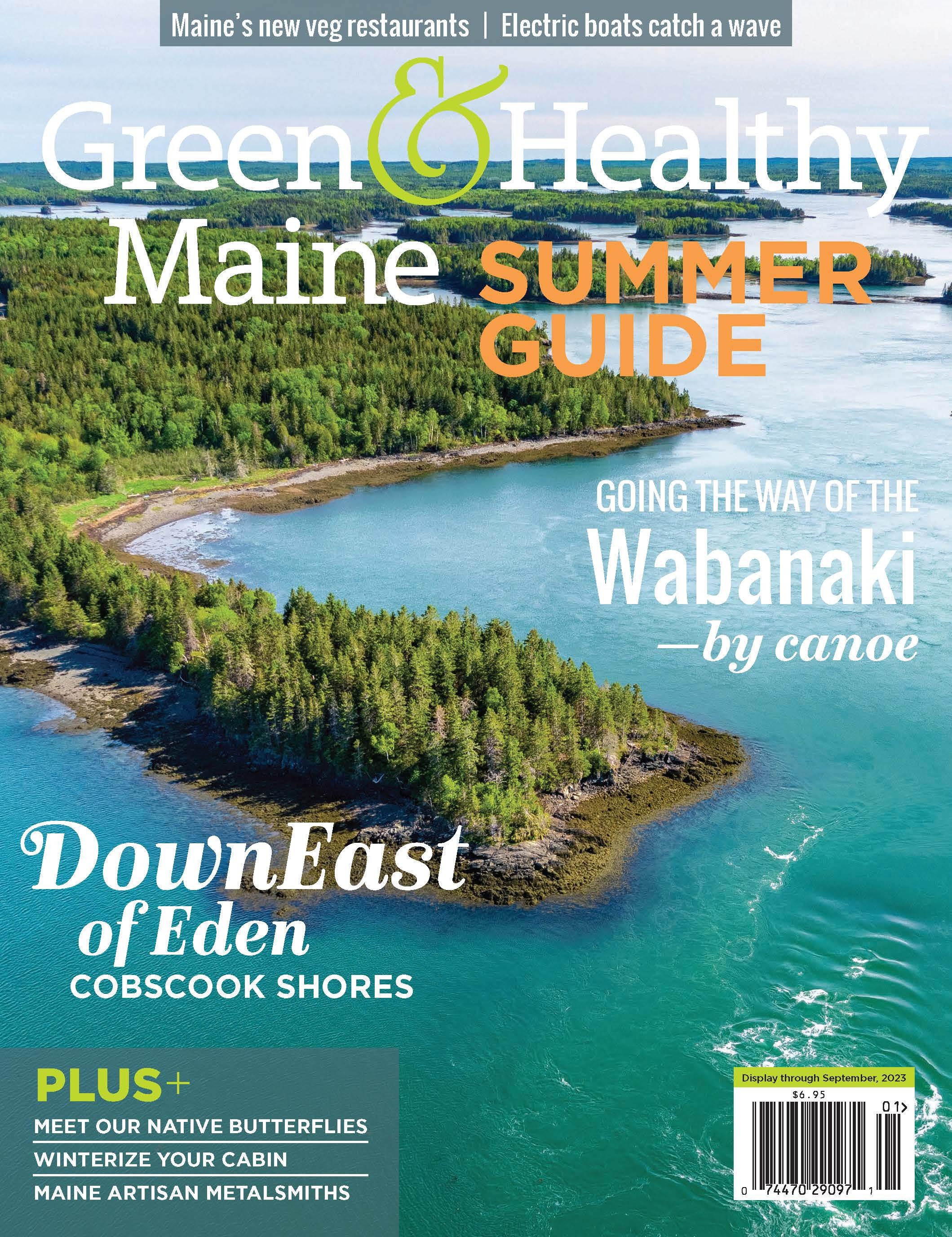

The parklands of Cobscook Shores, a landscape-scale conservation project, protect 16 miles of pristine shore front on Cobscook Bay, as well as its tributary arms of Dennys Bay, Whiting Bay, Straight Bay, South Bay and Johnson Bay. PHOTO: CHRIS SHANE

By Carey Kish

IN FAR DOWNEAST MAINE, about 3 miles west of the Lubec waterfront, an arching black steel gate marks the entrance to Red Point Nature Preserve. A pleasant gravel lane beckons, leading into parklike terrain that was once cleared farmland. Much of the property has been reclaimed by forest, but some lovely meadows and orchards remain, including what may be Washington County’s oldest apple tree, which is thought to be around 200 years old.

The passage from Red Point to Red Point Island can be accessed except for an hour on either side of high tide. PHOTO: CAREY KISH

The short passage from Red Point to Red Point Island, accessible except for an hour or so on either side of high tide, is negotiated via a series of stepping stones. Once across, you find a narrow footpath winding through woods heady with the scent of spruce and eventually culminating at Little Point and an expansive view up South Bay. No signs of civilization are evident along the rocky shore cloaked in pointed conifers, just bluebird skies, sea-green water and brown tidal flats.

Red Point Nature Preserve is one of 20 parklands on 900 acres owned by Cobscook Shores, mostly in Lubec but also in neighboring Whiting and Dennysville. Cobscook Shores is a family-funded Maine charitable organization that is part of Butler Conservation, Inc. (BCI). This private foundation was established by visionary conservationist and environmental philanthropist Gilbert Butler, who has long, strong ties to Maine, where he has spent a part of every summer for more than seven decades, exploring the state’s woods and waters from his family home in Northeast Harbor on Mt. Desert Island.

The Cobscook Shores parklands protect a remarkable 16 miles of pristine shorefront on Cobscook Bay as well as its tributary arms of Dennys Bay, Whiting Bay, Straight Bay, South Bay and Johnson Bay. The name “Cobscook” derives from the Passamaquoddy word “Kapskuk,” which translates to “place where the water looks as if it is boiling.” Spend some time in these parts with their incredible rushing and roiling 24-foot tides and you’ll surely see why.

“The Cobscook Bay region has a wealth of existing conservation lands, and its spectacular geography includes a complex shoreline of bays within bays and coves within coves. The local fishermen and clammers always knew how beautiful it was, but not the general public,” says Charlie Howe, Director of Parks for BCI. “We wanted to create a complementary system of parks to add more public access and opportunities for low-impact recreation.”

A hiker on the Shore Trail at Black Duck Cove Park. PHOTO: CAREY KISH.

Cobscook Shores quietly opened its first parklands in 2020, but the word is out, and the organization estimates that last year about 5,000 visitors enjoyed exploring this bounty of beautiful properties, mostly on foot. The long-term goal is to attract 1% of Acadia National Park’s four million annual visitors, or 40,000 people each year, who would not only enjoy the amazing landscapes but also shop, eat and stay in the vicinity.

Since its 2015 founding, Cobscook Shores has invested $16 million in what BCI terms this “landscape-scale” conservation project, including $5.5 million in land acquisition and $11.5 million in improvements in the greater Cobscook Bay region. Perhaps its greatest impact, though, has been the one it’s had on the area’s young people. Last year, some 1,500 students from eight area schools enjoyed free guided outdoor recreation experiences, complete with all the necessary gear.

“The Cobscook Shores Outdoor Education Program is designed to work with the school calendar. In spring there’s biking, in autumn there’s paddling and we’ve now expanded into snowshoeing and cross-country skiing in winter,” says Howe. “We’re connecting them with nature and creating life-long healthy habits. The return for us is having the kids out there enjoying and appreciating our lands through fun physical activity.”

Screened- pavilions with tables and chairs dot the trails at Cobscook Shores. PHOTO: CAREY KISH

Visiting Cobscook Shores

For visitors new to Cobscook Shores, a good plan is to start at Old Farm Shorefront Park in Lubec, which serves as a visitor center of sorts. Explore the trails and structures here, and you’ll begin to get a real sense of the high level of detail that has gone into every aspect of this monumental endeavor. From the screened-in pavilions to the roadside wayfinding signs and trailhead kiosks, clean vault toilets and cold water fountains to the exceptional trail design, construction and signage, it’s no wonder these special places are called “parklands.”

The public can use Cobscook Shores family-friendly parklands free of charge, including picnicking, biking, paddling and walk-in camping. For hikers, however, the 18 miles of outstanding footpaths are the big attraction. And there are more miles in the works. Black Duck Cove is the largest park and sports a nearly 5-mile out-and-back hike on the Shore Trail, while sizable Race Point features 3 miles of wonderful walking. Shorter, easier trails abound.

“We’ve designed our trails to allow people to really experience the wild and undeveloped shoreline. They’re constructed in a sustainable manner to minimize erosion and reduce repairs long term, avoiding steep slopes and hydric soils and building durable structures to navigate these sensitive areas,” notes Howe. “We use local cedar and hemlock for trail structures, and reuse wood chips for trail surfacing. And we employ local firms and labor as far as possible.”

In addition to Cobscook Shores, BCI is also active at two other locations in Maine. Along the free-flowing East Branch of the Penobscot River southeast of Baxter State Park and Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, Penobscot River Trails protects 5,000 acres and 8 miles of river corridor, featuring a 16-mile system of multiuse trails. Due north a few miles, BCI has also protected a good stretch of the Seboeis River, the East Branch’s wildest tributary, and opened the new 7-mile Seboeis Riverside Trail.

BCI is an extraordinary organization that is not only benefiting the state of Maine but is implementing its innovative model of landscape-scale conservation in five other legacy geographies, from New York’s Adirondack Mountains and Shawangunk Mountains to the Black River in coastal South Carolina to the Patagonia regions of southern Chile and Argentina. One might suspect its extraordinary work is only just beginning.

Learn more

Cobscook Shores

cobscookshores.org | (207) 400-0015

Penobscot River Trails

penobscotrivertrails.org | (207) 746-5807

Seboeis Riverside Trail

penobscotrivertrails.org/seboeis-riverside-trail

Butler Conservation, Inc.

butlerconservationfund.org | (212) 303-0208

On the cover: In far DownEast Maine, the parklands of Cobscook Shores protect miles of pristine shorefront.