Seaweed, the superfood

Seaweed adds flavor, boosts nutrition and supports Maine’s local economy

Micah Woodcock harvests wild alaria off Stonington. Photo: Greta Rybus

By Amy Paradysz

Omega-3s, calcium, protein, fiber and iodine: Seaweed has it all. Few things are good for you, good for the environment and good for the local economy. But at that intersection, there’s seaweed.

“I call it the trifecta,” says Mitch Lench, the entrepreneur who founded Ocean’s Balance in 2016. The Biddeford-based business farms and wild-harvests seven species of organic seaweed included in an innovative line of products.

The Ocean’s Balance product line includes marinara and arrabbiata sauces (Mariner’s Marinara and Mariner’s Arrabbiata), a simple way to incorporate the health benefits of seaweed. The same is true of their kelp-containing spice blends with no added salt—Seaweed Seasoning for Seafood, Lemon Pepper and the 2022 Gold sofi™ (Specialty Food Association) award winner in the spice category, Chili Lime.

“Our first product we came out with—we still sell it—is called Kelp Puree,” Lench says. “It’s an easy way to put kelp into your everyday diet by putting it into soups or stews. We have since shifted our focus away from strictly seaweed aficionados, who might have been eating seaweed since the 1970s, to people who want things that are easy. If I don’t know exactly what to do with an ingredient, it sits. The gateway is things that are easy to use, like pasta sauce with seaweed in it.”

They’re onto something: Ocean’s Balance sales totals have doubled annually for the past three years, reaching over $1 million annually.

“We have an experienced distribution team, which was one of the things that was missing from the seaweed industry,” Lench says. “Everyone wanted to be a farmer, but we also needed to educate and create new markets for seaweed.”

Ocean’s Balance is one of a dozen companies on the Maine Seaweed Council, composed of harvesters, researchers, processers, and makers of a range of products, from North American Kelp’s soil conditioners to Dulse & Rugosa’s Seaweed & Roses facial scrub. The food-focused companies tend to split into two camps: wild harvesters, like Atlantic Holdfast, and aquaculture farmers, like Springtide Seaweed. Both camps, though, are drawn to the health, environmental and economic promise of seaweed.

Wild harvester Micah Woodcock of Atlantic Holdfast

“Maine is the seaweed breadbasket—or the kelp basket—for half the country,” says Micah Woodcock, who founded Atlantic Holdfast Seaweed Company a decade ago. “There’s not much other harvesting or production on the East Coast.”

Woodcock apprenticed for two years under longtime seaweed harvester Larch Hanson of Steuben, who has trained several other small-scale harvesters. It didn’t take long for Woodcock to realize he loves living by the intertidal rhythm, donning a wetsuit and taking out his boat at low tide, whether that’s at 2 p.m. or 2 a.m. He has a small crew with boats going out of Stonington, harvesting sea vegetables that have thrived in that strong current for millennia: dulse, sugar kelp, kombu, wakame, bladderwrack and Irish sea moss. They sun dry, package and market whole-leaf and flaked products, which are available online and at food co-ops in Belfast, Blue Hill and Portland.

“The easiest way to incorporate seaweeds into your diet is to put a small amount in savory recipes,” Woodcock says. “It’s not about making it a seafood dish. You can put it in a chowder or fish stew, but you can also put it in a pot roast or beans to enhance the flavor and add a nutritional boost. The flavor enhancer MSG is a synthetic replica of naturally occurring glutamates in kelp, which means that adding small quantities enhances other flavors.”

Most Americans first try seaweed in Japanese food, like the nori used to wrap sushi wrap, bits of ogonori in seaweed salad or kombu in the broth of miso soup. Woodcock is interested in what he’s heard called the “de-sushification” of seaweed, including returning to older New England traditions. Many of us have been to an old-fashioned Maine lobster bake, the crustaceans steamed over hot coals and wet rockweed. But Woodcock suggests baked beans flavored with bits of kombu (with or without the more traditional flavor of bacon). Or grilling fish wrapped in kelp—and eating both. Some of the recipe photos on his website are more on the adventurous side. Case in point: An octopus-shaped mold of Irish sea moss chocolate pudding.

“People used to do more with seaweed in Maine, especially in Washington County and further Downeast,” Woodcock says. “Irish moss is a thickener and, historically, one of the things people would do with it was make Irish moss pudding. You reconstitute the Irish moss in fresh water, rinse it really well and simmer it in milk for 20 minutes or so, and the carrageenan is released. Then you take the seaweed out and add other flavorings. I usually do blueberries and maple syrup—just keep it simple for people to try. And, as it cools, it sets like jello.”

But we’re getting a bit far out in the weeds.

Back to sustainability: The Department of Maine Resources licenses wild harvesters, who report “their landings”—that is, where, what and how much they harvest. In addition to that state-sponsored environmental oversight, harvesters say that nature herself has designed seaweed to be a sustainable resource. “A lot of seaweed harvest is in rough waters,” Woodcock says. “There are places where I’ve tried to harvest that are just too difficult, and you can’t get to the places where seaweed grows for much of year.”

Dr. Carrie J. Byron, associate professor at University of New England’s School of Marine and Environmental Programs, says, “There has been some work looking at the effects of harvesting wild rockweed (Ascophyllum nodosum). The industry uses practices that follow the best available science. There has been very little to no research done on other species of wild-harvested seaweed. The total take is so low in the state of Maine . . . If the scale of harvest were to change drastically, then we may have a sustainability issue, but we are not in that place right now.”

On the other hand, she says, there is clear evidence that seaweed aquaculture is beneficial to the environment.

“Seaweed farming provides several ecosystem services,” Byron says, explaining that it offers nutrient and carbon cycling and can create habitat for wild organisms. “And seaweed farming provides a cultural service. Many Mainers identify with working on the water. Farming or harvesting seaweed is a way to connect with that cultural heritage.”

Maine Coast Sea Vegetables, founded in 1971, processes sugar kelp (shown here) as well as dulse, alaria, laver, sea lettuce, bladderwrack and Irish moss. Photo: Kelly Hinkle.

Aquaculture farmer Sarah Redmond of Springtide Seaweed

Back when she was in high school, Sarah Redmond wanted to be a seaweed farmer—and hoped that it would be “a real thing.” Today, it is. “We learn from the wild, natural systems and learn how to enhance and cultivate it and create new abundance,” Redmond says.

Springtide Seaweed, the largest organic seaweed farm in North America, grows four varieties, including dulse, shown above. Photo: Sarah Redmond.

She earned a master’s degree in marine botany from the University of Connecticut, co-founded the now-defunct Maine Seaweed Festival and worked as an extension agent for Maine Sea Grant. Then, in 2017, she leased part of Frenchman’s Bay at the foot of Acadia National Park and started growing seaweed. From her production facility in Gouldsboro, she looks across the bay at Cadillac and Acadia mountains. It’s very important to her that what she’s doing helps the natural environment.

“I’m essentially growing, for lack of a better word, a forest every year,” she says. “I have so many lines and I’m growing, let’s say, hundreds of thousands of pounds of photosynthetic algae forest. That creates photosynthesis in the ocean, taking up carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus, and creating oxygen and habitat. And then I remove the reef at the end of the year. I’m trying to help rebalance the ecosystem where we have created imbalances.”

At the same time, Redmond produces roughly 100,000 pounds of food per year. “It’s not hard to produce tremendous amounts of seaweed—and during the winter too,” she says. “You provide the moorings that hold the rope in place, put out the seed, and then you get this incredible growth every year in eight months or so.”

Redmond untangles lines that got crossed in storms. If lines get heavy and sink, she adds buoys. If they rise to the surface, she adds weights.

“The ocean does the rest,” she says. “The saltwater and the minerals naturally present in the seawater, and the sunlight. We have this body of water with all the elements that make for really good seaweed. Arguably, sustainably farmed seaweed from Maine is the finest in the world.”

Enterprising lobstermen and -women are finding seaweed aquaculture provides a viable second income and that they already have most of the tools and skills.

“There’s a lot of potential for seaweed farming as a way for our maritime heritage to continue in rural areas,” Redmond says. “Owned and operated by local people.”

There’s the trifecta: Seaweed aquaculture is good for the sea, good for the coastal economy and, definitely, good for us in a nutritional sense.

“Seaweed is a plant or an algae in the ocean that has the amazing ability to pull out all of these very dilute trace minerals and concentrate them into their tissues,” Redmond says. “So you have mineral contents that are like ten times higher than land plants. But it’s also a ‘seafood.’ So you get all these nutrients that are unique to seaweeds because they live in the sea that can help enhance and supplement your diet. It’s a very interesting food.”

Sarah Redmond working her aquaculture farm in Frenchman’s Bay. Courtesy photo.

Let’s get cooking!

Barton Seaver, a Maine-based chef and author of Superfood Seagreens: A Guide to Cooking with Power-Packed Seaweed, contributed this Miso Soup recipe. Many Americans are familiar with miso, as it is a traditional appetizer in sushi restaurants the country over. With its warming and hearty flavors of fermented miso, rich with umami flavor, and gentle nuanced broth, this soup is simple to prepare in just a few minutes. The recipe below makes a wonderful base on which to build your own creations—just add tofu, fresh herbs, chicken, seafood, or whatever you like. Makes 1 gallon.

Miso Soup

INGREDIENTS

2 ounces shredded dried seagreens (alaria, wakame, nori)

1/4 cup bonito flakes

1 cup red miso paste

INSTRUCTIONS

Bring 1 gallon water and shredded sea-greens to a gentle simmer in a 6-quart saucepan. After 20 minutes, remove the greens with a slotted spoon and reserve them for another use. Add the bonito flakes. As soon as the broth returns to a gentle simmer, remove the pan from the heat and strain. Stir in red miso paste and bring to a simmer. Optional garnishes: enoki mushrooms, scallions, diced tofu.

Mmm, more seaweed

Atlantic Sea Farms

atlanticseafarms.com

Biddeford-based Atlantic Sea Farms made Fast Company’s 2022 Brands that Matter list after they launched a line of frozen Sea-Veggie Burgers (ginger sesame and basil pesto). They also sell refrigerated jars of Fermented Seaweed Salad, Sea-Beet Kraut (a take on sauerkraut) and Sea-Chi (a take on kimchi).

Cup of Sea

cupofsea.me

Teas handcrafted in Portland incorporating wild-harvested seaweed from the Gulf of Maine.

Maine Coast Sea Vegetables

seaveg.com

This Hancock-based business sells nine types of seaweed, each in multiple forms—granules you might sprinkle like Parmesan cheese, powders you might include in a smoothie and milled products you might use as you would spices.

SeaMade

Convenient and nutrient-rich Cranberry Almond & Kelp bars, produced at Fork Food Lab in Portland.

Sailor's Cure-All, a ginger, turmeric and bladderwrack tea blend by Cup of Sea. Courtesy photo.

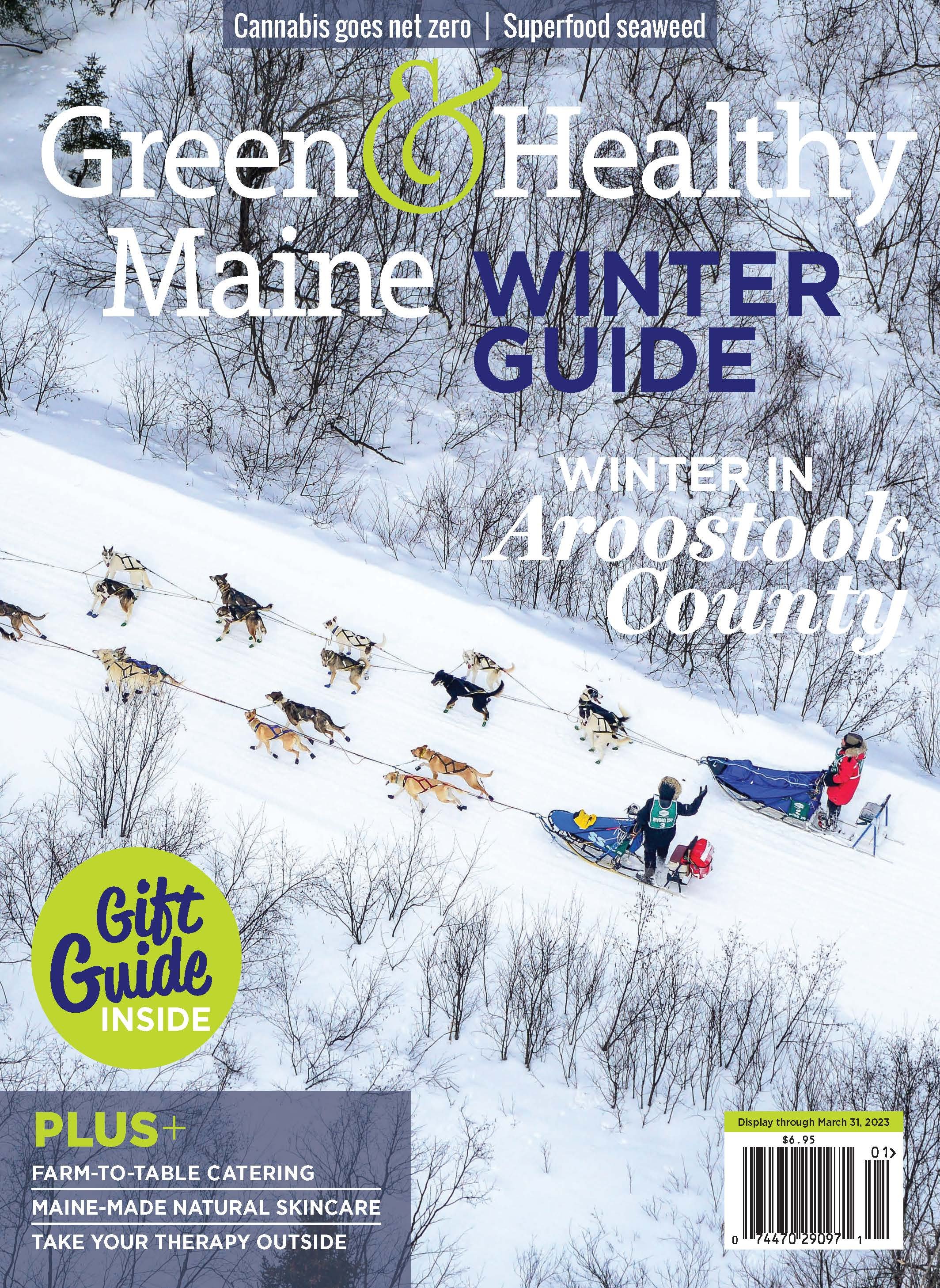

On the cover: Mushers and their dog teams on the course of the Can-Am Crown International Sled Dog race in Fort Kent, Maine.