Cannabis goes net zero

Solar-powered Upward Organics on track to be Maine’s first net-zero cultivator

Nate Burdick cleared this patch of woods in Porter to set his outdoor cannabis plot on a slight hill for just the right amount of breeze. Photo: Karen Alterisio.

By Amy Paradysz

HERE’S WHY WE SHOULD CARE about cannabis cultivation even if we don’t smoke it: It’s Maine’s most valuable crop. And most cannabis here is grown indoors in controlled settings, making it highly resource intensive. To put University of Colorado stats in in some perspective: Growing one pound of dried cannabis flowers indoors in Maine is the carbon equivalent of driving a car that gets 25 miles per gallon from Portland, Maine to Juneau, Alaska.

But it doesn’t have to be, as Nate Burdick is proving.

Burdick, 36, is the owner and operator of Upward Organics, a licensed medical grower in Porter. He’s months or even weeks away from being able to quantify that he’s running Maine’s first carbon-neutral cannabis growing operation.

“Somebody has to be first, right?” he says. “Hopefully, there will be many more.”

A dirt road in rural Oxford County winds uphill and opens to a clearing, where rows of towering cannabis plants grow, each in there own structure. From a distance, the plot looks like a vineyard.

It’s set on a slight hill, creating a breeze that blows away pathogens and keeps insects from getting too comfortable.

Multi-purpose garage designed by BRIBURN Architects. Courtesy photo.

Behind two greenhouses and other outbuildings is what Burdick dubs the “Garage Mahal,” a barn-style building with a drying room, a solventless lab and other workspace. Burdick and his fiancé Kate Gollon (a veterinarian) are living in an apartment on the second floor with two dogs and three cats while their modestly sized eco-friendly home designed by BRIBURN Architects is being built next store.

Originally, Burdick planned to be off-grid, in part because of the length of their driveway. But by his fourth growing season, it was apparent that even a small, sun-grown cannabis farm has significant electricity needs. Balancing ecological and economic concerns, he decided to connect to the grid and expand his existing array of 15 solar panels to try to reach net-zero energy use.

This fall, he worked with Maine Solar Solutions to find that balance, adding 10 Silfab 490-watt panels. Together, the system will offset the equivalent of 16,600 pounds of carbon dioxide annually—or enough to run the farm.

Now that Burdick has an electric meter, he plans to use social media to be transparent about his journey to net zero. It’s likely that when he and his fiancé and menagerie move into their home when it is fully constructed next door in spring 2023, Upward Organics will be carbon neutral.

“Of course, if we grow our business again, that could change things for a bit,” Burdick says. “It’s a fluid situation, which is what makes it a fun challenge.”

When asked how he got here—growing cannabis the most sustainable way possible on his off-the-beaten-path 22 acres—Burdick says it’s a funny story. He was in software sales in the Boston area but was always happier outdoors, running, biking, hiking or surfing, often on trips to Maine. A friend’s brother who was growing cannabis in Maine knew Burdick grew up doing landscaping and asked if he wanted to help trim the flowers.

“I did that,” Burdick says. “And then he was like, ‘I’m going away for a week. Can you water my plants?’ And I did that. And then he was like, ‘I’m taking off for the winter. Can you come watch my house?’ And then it was, ‘If you quit your job, I’ll cut you in and we can double the size of our farm.’ So it was a slow progression.”

Then in 2017, Burdick bought land in Porter to start his own business.

“My friend Jim [Labadee] and I lived in this camper,” he says, pointing to a 32-foot 2004 Keystone Sprinter. “We cleared the land, and we started out growing 30 plants in this field. Jim had worked in the vineyards in New York and taught me how to be a farmer.”

Maine Solar Solutions installed 10 Silfab 490-watt panels on Upward Organics’ garage—estimated to be enough for the medical cannabis farm to reach net-zero energy use. Photo: Karen Alterisio.

They installed a Blumat watering system that gives each of the 60 outdoor plants the water they need, instead of flooding all the plants at once for a set period of time, saving both water and labor.

“The irrigation system uses a ceramic cone,” Burdick says. “It’s a sensor into the soil. As the soil dries out, the pressure on the cone reduces and a spring-loaded top opens up and lets water out. As water enters the soil, pressure increases on the spring and the water is cut off.”

It works perfectly—most of the time. “But this year, because of the drought, mice came in and chewed holes through everything,” he says. “We had to shut it off and hand-water. But the theory is sound.”

After installing the watering system for his outdoor plants, Burdick built what every farmer in Maine wants: a greenhouse. He bought it secondhand from Skyline Farm in Yarmouth in 2021, reassembling it beside his cannabis plot in the quiet of winter.

“Right now, we’re running just fans and exhaust; we’re using the sun instead of lights,” Burdick says, leading the way into the 30- by 36-foot greenhouse known as Alpha. “The plants need about 18 hours of sunlight to stay where we want them in the vegetative state, continuing to grow branches without growing little flowers. In March and April, we’ll add light to make the days longer. We have three supplemental lights. Then in June or even in May, we’ll close this tarp to black out the greenhouse and make the plants think it’s August or September. That’s how we can get two harvests a year, harvesting about half a pound per plant.”

To heat Alpha, Burdick uses hot water. “We put a furnace in,” he says, adding that his neighbor has a sawmill and drops off pine slabs and rounds. “There’s a big fire box in here surrounded by 370 gallons of water. This water is 173 degrees, and there are pipes that run underground that go to Alpha and to our shipping container. When either need heat, a radiator turns on and blows air across copper pipe with 185-degree water in it.”

Alpha ran off-grid for four years, by which time Burdick was done constructing his second greenhouse, aptly named Beta. As one might expect, Beta is even more innovative.

“We put in two Ground to Air Heat Transfer, or GAHT systems,” Burdick says. “Greenhouses produce heat. Instead of exhausting the heat outside—which the world doesn’t need—we put that heat underground. When the temperature in the greenhouse gets up to 85 degrees, this GAHT system kicks on. It pumps 85-degree air down, and it comes up as colder air. The air comes out of here at about 65 degrees, cooling the greenhouse during the day. But then at night, when it gets to 48 degrees, the system pumps 65-degree air up here. So we’re keeping the greenhouse from getting too hot or too cold—with just the use of fans. No propane or oil burner or wood furnace.”

Essentially, he’s putting his greenhouse’s gasses to work inside this 24-foot by 72-foot world to avoid creating greenhouse gasses in the outside world.

Watermelon Thundersnow is a unique Maine hybrid that smells a bit like watermelon and was first harvested during a strong early season snowstorm with thunder. It’s one of a few dozen varieties grown at Upward Organics. Courtesy photo.

“I got so nerded out and so obsessed with this,” Burdick says. “We’re walking over all this piping that’s buried at two feet, four feet, six feet and eight feet underground. We dug a massive hole and laid all this pipe and covered it with dirt before we built the greenhouse.”

Inside, 30 plants as tall as Burdick himself grow in raised beds. Cover crops—grasses, vetch and radishes—fix nitrogen into the soil. Burdick cuts them down now and again, and red wrigglers eat the green matter, putting nutrients back into the soil to encourage maximum growth.

“We can only grow so many plants,” Burdick says, “so we use trellises on bamboo stakes to grow them big. We pull them down when we need them and pull them back up when we don’t.”

When it’s time to harvest—in October outdoors and in November and June indoors—both sides of the family come up to stay in the Garage Mahal and pitch in.

Burdick is the only person who works the farm full-time year-round, spending much of his days outdoors from April to November with his spotted dog, Goose, trailing behind him. “Then November to the first week of April, I’m doing business development, selling, handling compliance and thinking about innovation,” he says.

He pauses, picks off a calyx of a unique Maine-bred hybrid called Watermelon Thundersnow, and takes a whiff.

“I’m passionate about the purpose that this company has, which is showing that you can provide clean, potent medicine without its being at the expense of the planet.”

Nate Burdick and his sidekick, a spotted rescue dog named Goose, after a hard day’s work. Photo: Amy Paradysz.

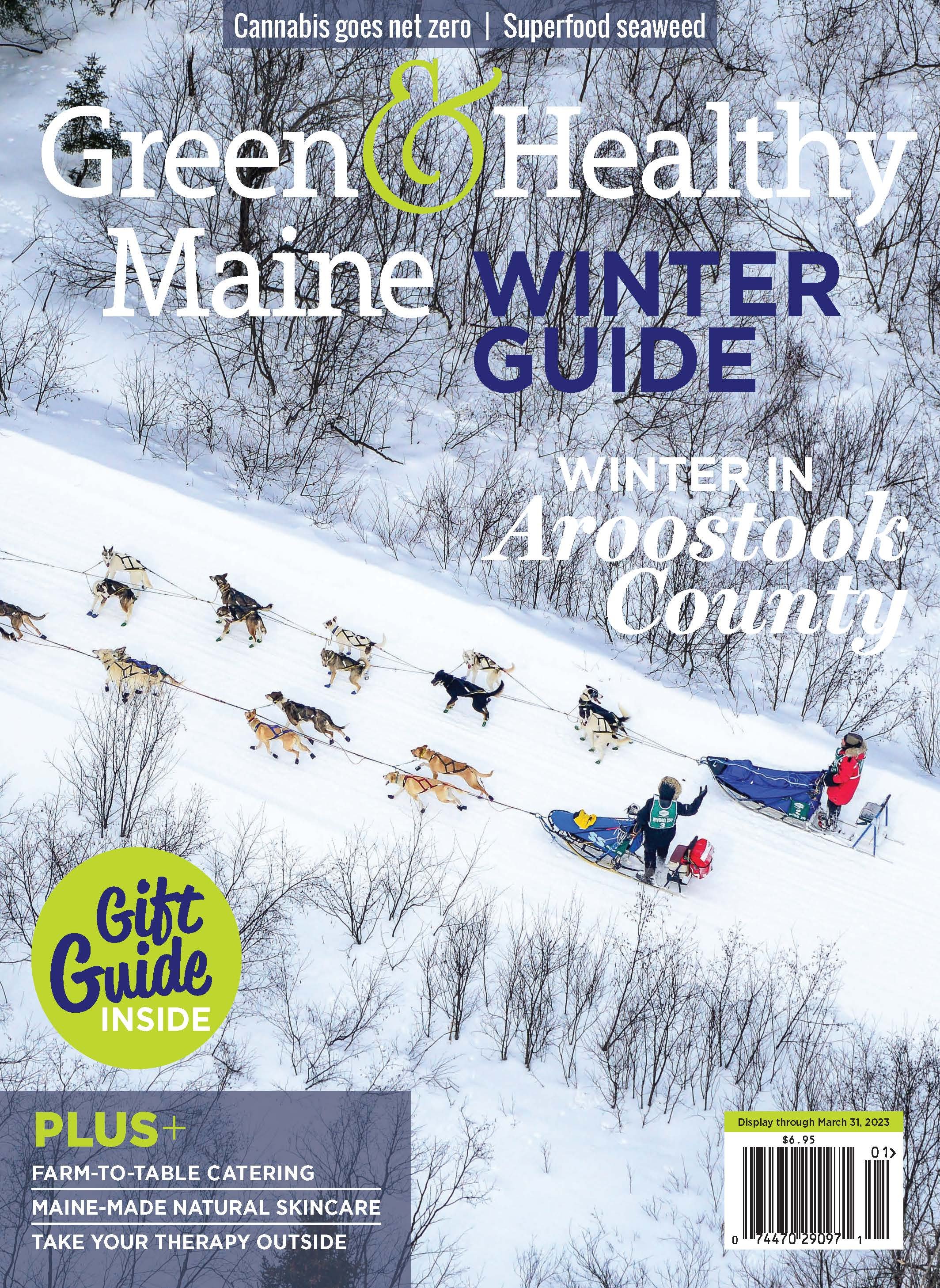

On the cover: Mushers and their dog teams on the course of the Can-Am Crown International Sled Dog race in Fort Kent, Maine.