Get to know Maine’s native butterflies

Plus, butterfly gardens where you can view these living jewels

American copper, Lycaena phlaeas

By Andrea Lani

Photos: Bryan Pfeiffer, except where noted

ONE OF THE HIGHLIGHTS of summer in Maine for me is witnessing the procession of colorful and lithesome butterflies that visit my yard over the season. I’m not very interested in growing vegetables, but I’ll happily plant more flowers to attract more butterflies.

In addition to offering endless pleasure to those who observe them, butterflies provide important ecosystem services, including pollinating wildflowers and horticultural plants; serving as prey for birds, small mammals and other insects; and as indicator species, with scientists using their relative abundance or absence as a tool to assess the health of their habitat.

Another important role of the butterfly is as an ambassador connecting humans to the world of insects, according to Phillip deMaynadier, a wildlife biologist with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. “Butterflies are a gateway group,” deMaynadier says. “People are only going to care about the things they know.” Our natural affinity for butterflies can lead to a greater appreciation of less beguiling and more difficult to identify groups of insects—such as flies, wasps and beetles—that play outsized roles in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

While most people are no doubt familiar with big, showy butterflies like monarchs and swallowtails, many would be surprised to know that Maine has about 120 different species of butterflies. These range over five families that include the generally tiny skippers (Hesperiidae) and gossamer-wings (Lycaenidae), the flighty whites and sulphurs (Pieridae), and the charismatic members of the brushfoot (Nymphalidae) and swallowtail (Papilionidae) families.

Butterflies undergo complete metamorphosis, meaning they have four distinct life stages: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis) and adult (imago). While adult butterflies can generally consume nectar from an array of flowers, deMaynadier notes, caterpillars can be quite specialized in their feeding habits, with some associated with just a few or even a single species of plant. This means that a significant number of butterfly species exist only in particular habitat types, such as bogs, barrens, stream sides, salt marshes or alpine areas. One example of a highly specialized species, the rare and endangered Hessel’s hairstreak (Callophrys hesseli), feeds only on Atlantic white cedar growing in a few swamps in York County.

Our knowledge of butterflies across the state largely comes from the Maine Butterfly Survey, an atlassing effort led by Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, in partnership with the University of Maine at Farmington, Colby College and other organizations. To establish the distribution and status of butterflies across the state, the survey relied on photographs and specimens collected over ten years by citizen scientists beginning in 2006.

Data from the survey, along with data from a similar project carried out in eastern Canada, will be published in October in the book Butterflies of Maine and the Canadian Maritime Provinces. Published by Cornell University Press, the book will serve as both a field guide and a scientific treatise on butterfly status and conservation in the Acadian region, as described by deMaynadier, who is the lead author.

Because the survey was the first of its kind in Maine, it established baselines but was not able to assess trends. However, in other states, such as Ohio and Massachusetts, where species’ increases and decreases have been studied, researchers have found a significant number of butterfly species in decline, according to deMaynadier. And a full 20% of Maine’s butterfly species are listed by the state as endangered, threatened, special concern or extirpated, meaning they no longer exist in Maine.

Sleepy Duskywing, Erynnis brizo

There is growing concern about declines in insect populations worldwide, notes deMaynadier. He adds that pressures on butterflies in Maine include climate change, pesticide use and habitat loss due to development. A surprising culprit in the decline of some Maine butterflies is ecological succession, in which habitat types such as grasslands and barrens revert to forest. Rare species dependent on barren ecosystems include the Edward’s hairstreak (Satyrium edwardsii) and the sleepy duskywing (Erynnis brizo). The eye-catching regal fritillary (Argynnis idalia) is one that has been edged out of Maine by forests growing up on former agricultural land.

Invasive species pose another danger to butterflies, deMaynadier points out. Invasive plants, such as purple loosestrife and phragmites, out-compete native wetland species, and insects, like the emerald ash borer and beech scale insect, damaging important host plants. Ash trees are a food source for the Canadian tiger swallowtail (Pterourus canadensis) and Baltimore checkerspot (Euphydryas phaeton) larvae. The caterpillars of the early hairstreak (Erora laeta), a tiny emerald gem of a butterfly, eat only the husks of the beechnut, and thus depend on mature beech forests to survive.

Gardening for butterflies

We can all play a role in improving the prospects for butterflies in Maine by creating habitats in our yards and using organic pest control methods instead of pesticides. DeMaynadier recommends that homeowners incorporate native plants into gardens and landscapes, providing food for both caterpillars and adult butterflies. The University of Maine Cooperative Extension provides a list of plants suitable for pollinators, including butterflies, as well as a Pollinator- Friendly Garden Certification program (extension.umaine.edu).

For landowners with larger properties, deMaynadier suggests managing open fields and pastures in a wilder state, with buffers of wildflowers and mixed shrubs between hay and forest, and mowing on a rotational basis to allow two years’ of growth between cutting.

Charlotte Rhoades Park & Butterfly Garden. COURTESY PHOTO.

Viewing butterflies in Maine

The best way to become better acquainted with Maine’s array of fluttering jewels is to spend time in the field when butterflies are active. While species that overwinter as adults, such as Mourning cloaks (Nymphalis antiopa) and Eastern comma (Polygonia comma), may appear on the first warm day in March, and monarchs can be seen as late as November, the best time to view butterflies in Maine is May through September.

Head out on a warm, clear day to your local land trust, public garden, a neighbor’s field or any place that has what butterflies need: sunny, open areas where pesticides are not sprayed, with abundant flowers and nearby woods and water. A pair of close-focus binoculars (under 10 feet) and a good field guide, such as Butterflies through Binoculars by Jeffrey Glassberg, will help you get a better look at and begin to identify the butterflies you encounter. Visit the same place frequently over the season to see a range of species.

As you become more familiar with butterflies, consider taking photos and uploading them to iNaturalist, an app that allows you to track your sightings, helps with identification and provides data to scientists. Many of the records mapped in Butterflies of Maine and the Canadian Maritime Provinces were “mined” from iNaturalist and other citizen science sources.

To experience what deMaynadier calls a “concentrated blast of excitement,” consider visiting a park or garden dedicated to butterfly conservation and education. They provide a variety of host plants for both caterpillars and adult butterflies as well as interpretive signs and volunteers to help you learn more about our winged friends.

On your journey to becoming a butterfly watcher and gardener, take time to read and learn about these insects, recommends deMaynadier. “They have an incredible story to tell.”

Maine butterfly gardens

Monarch, Danaus plexippus. COURTESY OF CHARLOTTE RHOADES PARK & BUTTERFLY GARDEN.

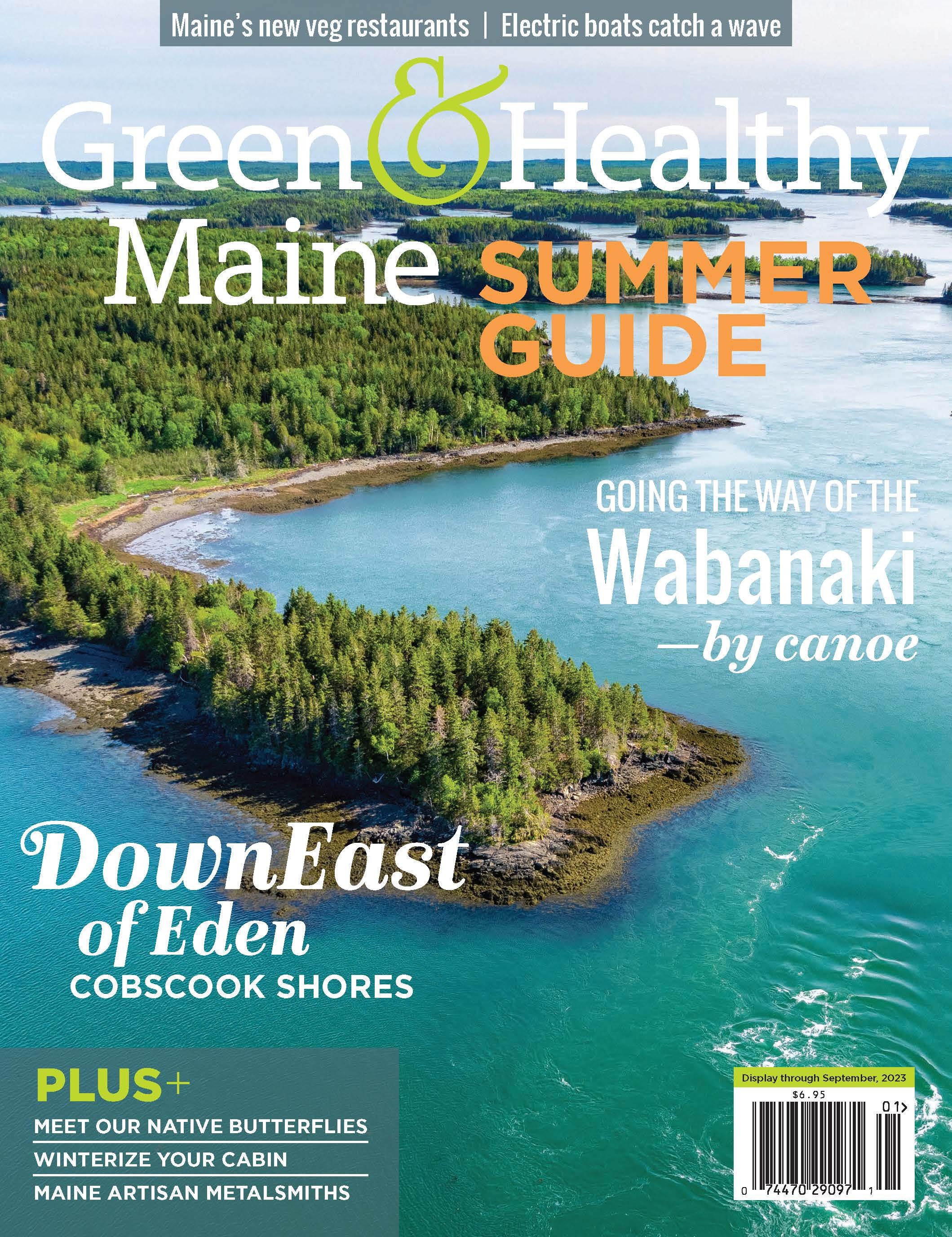

On the cover: In far DownEast Maine, the parklands of Cobscook Shores protect miles of pristine shorefront.