Stories in the Snow: Tracking Maine wildlife in winter

IN THE QUIET OF WINTER, when insects have ceased their buzzing, migratory birds have flown south and frogs have settled into hibernation, it’s easy to imagine we humans have Maine all to ourselves, aside from a handful of year-round birds and the squirrels who raid the feeders we put out for those birds.

By Andrea Lani

In fact, we’re surrounded by nearly 60 species of wild mammals, most of which stay active in winter. While a few of Maine’s mammals hibernate or go into a dormant state in wintertime, the majority carry on hunting, foraging and going about their business as they have all year, out of sight and out of mind.

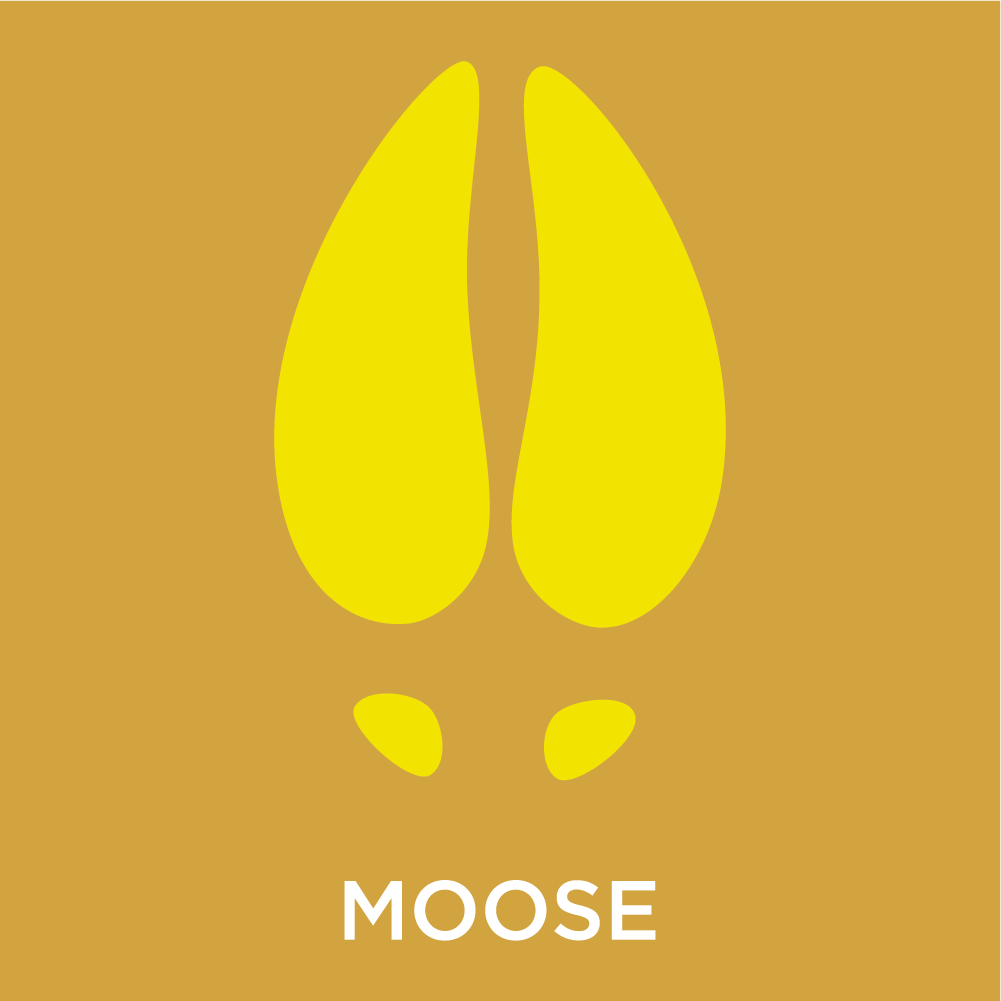

We rarely see the wild mammals who make Maine home because most of them are active primarily at night (nocturnal) or at dusk and dawn (crepuscular), including bobcats, deer, moose, racoons, opossums and most species of weasel. This makes observing mammals in the wild a challenge for us diurnal humans. Fortunately for aspiring naturalists, wildlife leaves behind traces—tracks, scat and other signs—that we can use to identify which animals have traveled through an area and interpret what they were doing while they were there.

While it’s possible to track wildlife any time of the year, winter offers boundless opportunities, with fresh snow after every storm creating a blank slate onto which wild animals trace their comings and goings. Tracking also offers a great way to get outside and enjoy a winter’s day while learning about what’s going on in the wild world. Think of tracking as turning a sedate snowshoe trek into a wildlife safari.

To get started tracking, according to Maine Master Naturalist Sandra Mitchell, all you need is curiosity. “You need to want to know about the critters you share the world with,” she says. “Go out and find a track in fresh snow that looks interesting. Start to ask questions—who might it be? What animal fits that size? Who would I expect to live here?”

Tracking requires little equipment beyond the warm clothes you would wear for a snowy walk. Dorcas Miller, noted Maine naturalist and author of Track Finder: A Guide to Mammal Tracks of Eastern North America and Scat Finder: A Guide to Mammal Scat of Eastern North America, carries with her a small pack holding a tape measure, a notebook, a pencil and a track identification guide or two. In addition to Miller’s guides, Mitchell recommends Mammal Tracks and Sign: A Guide to North American Species by Mark Elbroch.

There’s also no need for beginning trackers to travel anywhere special. “Your very own backyard, even if it is small, is a great place to start learning to track,” Mitchell says. “You probably already know what animals spend time there.” Once you get familiar with the tracks that crisscross your yard, you may want to move farther afield. Miller notes that “some places are richer in tracks, scat and sign than others. Look for an area with a surface that preserves detail—such as snow, mud or damp sand—as well as a site where animals tend to feed or travel, such as in the corridor along a stream or along a pond.”

After following the trail of a porcupine, Greater Lovell Land Trust's Tuesday Trackers rejoiced when they found a huge pile of scat that revealed the den site. PHOTO: LEIGH MACMILLEN HAYES

Miller recommends heading out tracking a day or so after a fresh snow, to give animals time to leave their traces. She notes that while you can identify patterns in deep snow, a thin layer of soft new snow on a firm surface, such as frozen ground or hardpacked snow, offers the best opportunity for seeing details in individual prints. “But, if you can see a track, you can puzzle over it,” Mitchell says. “So don’t limit yourself to ideal conditions.”

Trekking on a snowshoe trail in winter is a great way to get your heart pumping; adding tracking to your outdoor adventures gets your brain in on the action. “Tracking is detective work,” Miller says. “You assemble clues and use them to see into the otherwise hidden lives of mammals.” Miller suggests taking notes and making sketches when you’re out tracking, both as a record of what you’ve observed and to help reinforce your learning.

Uncovering the identity of a mammal from its tracks is a matter of looking at the size and shape of individual prints, the width of the trail, and at the pattern formed by a series of prints, according to Miller. “Each animal has a favored gait, which creates a characteristic pattern,” she notes. For instance, the tracks of animals that bound, like mice, squirrels and hares, form a box or triangle. Long-legged animals like deer, cats and coyotes leave behind a zigzag-shaped trail. Short-legged, waddling animals like porcupines create a trough. And the prints of animals in the weasel family show up as paired diamonds.

David Brown's Trackard sketch of fisher prints are a perfect match to the real thing found in the snow. PHOTO: LEIGH MACMILLEN HAYES

The first thing to do when coming upon new tracks, Miller says, is to zoom out and look at the big picture, as if you were observing the tracks from above. “What pattern do the tracks form?” Then zoom in and study groupings of prints. Finally, look very closely at individual prints, noting the texture of the edges, the presence or absence of nails and other fine details. Look also for other clues, such as scat, hair or quills, and acorns, pinecone scales and other meal leftovers.

To learn even more about the life stories of the animals who share our world, study places where the tracks of different species intersect, suggests Miller. Try to determine whether they came by at different times or if they interacted in some way. Was one predator and the other prey?

Wildlife tracks offer a wealth of information to those who look closely. “Depending on the animal,” Mitchell says, “you can identify the species, often the sex of the animal, sometimes its age, what it eats, where it sleeps, who it is afraid of, who is afraid of it and what resources are most important to it.”

Like with many activities, wildlife tracking is more fun with a buddy. Mitchell notes that she got into the activity by going bobcat tracking with a friend. “One day following a bobcat and I was hooked for life,” she says. A great way to meet other people who enjoy following animal tracks through the woods, as well as for novice trackers to learn more, is to attend a tracking program or go on a tracking hike led by an expert. Check with Maine Audubon, your local land trust or nature center, or a state park to find a tracking program near you to attend this winter.

Wildlife tracking opens a whole new window into the secretive world of Maine’s mammals. “I really enjoy being able to see the world as the animal sees it and trying to sense what they were thinking as they went about their daily life,” Mitchell says. “It isn’t so much about simply identifying an animal. It is more about determining what they were doing and, most interestingly, why. It is a way to spend time with that animal without inserting myself into the equation or interfering with it in any way. You learn so much about a species—and the individual you are following—just by taking the time to slow down, look around and become that animal in your mind.”

On the cover: Judi steps out of a cabin in the 100-Mile Wilderness to fresh falling snow.