It’s all in the wood: Tradition meets innovation in Maine summer theater

The wood interior of the Arundel Barn Playhouse echoes generations of voices. Photo: Courtesy of Arundel Barn Playhouse

By Bob Keyes

Adrienne Grant, the artistic director at the Arundel Barn Playhouse in southern Maine, always thinks of wood when she thinks of summer theater. Old, worn wood that retains the character and heritage of the family that made its livelihood in the rugged barn that now houses the theater, and by the characters who have trod the stage there. On quiet mornings before a show, when a summer mist rises from the surrounding fields and crickets sing their songs, Grant sometimes finds herself alone in the barn. She wonders if she hears the voices of actors in a rousing, show-stopping chorus.

The wood soaks it up, and exhales it back. “The wonder of wood affects people upon entering, even though they may not know exactly what it is that is warming them,” she said. “It’s wood. It’s natural. It’s cozy.”

Summer theater has a long tradition in Maine, dating to the days when vacationers traveled here by rail, boat and car for idyllic holidays in rustic cabins and grand hotels that dotted the coast and inland lakes. From Ogunquit to Boothbay, Harrison to Skowhegan, theater offered more than just entertainment. It was a social outlet, an opportunity to come together after a day on the water. The perfect nightcap, if you will. Theaters hired New York stars, who readily accepted the opportunity to work in America’s vacationland.

That tradition is changing, but remains intact. Arundel Barn and theaters like it across the state still draw rising and established stars from New York, and audiences still fill the seats. But with entertainment options expanding and generations of vacationers growing up without a history of attending theater, Maine playhouses face the challenge of reaching new audiences while holding fast to the traditions that made them popular in the first place.

Hackmatack Playhouse founder Michael Guptill and artistic director Crystal Lisbon discuss the season outside the barn-theater in Berwick. Photo: Bob Keyes

They are doing that in many ways. The big theaters—Ogunquit Playhouse and Maine State Music Theatre in Brunswick—are staging much larger shows and engaging actors with star-power. They use their marketing savvy and social media clout to sell tickets year-round, and Ogunquit has extended its season from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

Others, like Arundel Barn, and Hackmatack Playhouse in Berwick on the New Hampshire border, are doing what they’ve always done, with good acting, fun shows and old wooden barns to draw people in.

Michael Guptill, who runs Hackmatack, remembers planning a season, hiring actors and selling tickets. It worked like magic. Now, he’s searching for new ways to entice people to come to his theater. He faces more competition for entertainment dollars and attention. Those are byproducts of changes in our society, and there are many more like it.

“Oh, it’s changed an awful lot,” he said on a recent spring afternoon. “One is simply the fact that people don’t plan ahead like they used to. We used to sell a lot more season tickets. We had people who wanted to sit in Row F, seats 16 and 17, on Aug. 16—and they were ready to make that decision in December. We sold absolute seats in December and January. We don’t do that anymore.”

Hackmatack Playhouse in Berwick is part of a working farm, occupied by generations of Guptills. They raise bison there now—and summer theater. Its rural character is a draw for many. Photo: Bob Keyes

Guptill depends more heavily on ticket sales to balance his budget, and finds creative ways to sell tickets. He’s working to attract group sales and becoming more active with social media, among other things.

Like Arundel Barn, Hackmatack offers atmosphere above all else. The theater is housed in a big white barn, one of several buildings on an immaculate property that’s been occupied by Guptill and his family for generations. His son raises bison in a field out back, and Gutpill encourages theater-goers to arrive early—and wear good shoes.

“We want it to be an enjoyable experience from the time they come to the time they leave. It’s not only the theater and the show,” Guptill said. “We offer ambiance and the whole atmosphere. We want people to bring a picnic, walk around into the fields and see the bison and maybe play a game of Frisbee if they want to.”

He plans shows what he thinks will appeal to an audience looking for a fun evening—nothing too dramatic or artsy. He schedules four shows each summer, and usually includes a non-musical or two. Audiences love fun musicals, easy comedies and titles they know. Figuring out what people want is never easy, and always a bit of a guessing game, he said.

“It’s a night out, but it’s a night out relaxing away from your cares and the world. We want people to sit back and enjoy the shows. That’s what summer theater is—a way to get out of the house in the summertime and enjoy yourself,” he said.

Legacy is big part of the summer theater experience. Ogunquit Playhouse has hosted shows since 1933, beginning in a renovated garage. The current theater, with its oval driveway, green awnings and well-kept grounds, opened in 1937.

Rashidra Scott, shown here in “Sister Act” at the Ogunquit Playhouse, is the latest in a long line of actors to come to Maine from New York to work in the summer. Photo: Courtesy of Ogunquit Playhouse

At Ogunquit, Walter and Maude Hartwig used their New York connections to bring shows to the beach town. They built the theater as we know it today. John Lane took it over in 1950, and it is now directed by Bradford Kenney, who has invested in the theater to expand its technical capabilities and raised the standard of the shows themselves.

In 1958, what is now known as Maine State Music Theatre opened in Brunswick. Victoria Crandall and later Charles Abbott—and now Curt Dale Clark—booked the shows, hired the talent and directed many of the productions, which were staged in Pickard Theater on the Bowdoin College campus. Pickard underwent a renovation in 2000, and remains the 600-seat home of Maine State today.

Clark began coming to Brunswick as an actor. When the opportunity to apply for artistic director came up, he jumped at it. He has rarely felt so warmly received as on the stage at Pickard. “I fell in love with how the audience embraces each and every show,” he said. “Up here, the applause seems to last longer than it does in most places.” In Madison, audiences have been giving standing ovations at Lakewood Theater since 1901, which bills itself as the oldest continually running summer stock theater in the nation. It’s another of those big, beautiful buildings, made with wood and filled with century-old charm and character. Herbert L. Swett, a Bangor native and Bowdoin graduate, presented the first play, “The Private Secretary,” in June 1901. He wanted a theater to provide entertainment for vacationers on Lake Wesserunsett. The theater has morphed into many things since, including hosting a repertory cast and booking traveling shows.

Today, it operates as a community theater that relies heavily on volunteers, said board member Stephanie Irwin. What has remained constant is the building itself. Lakewood has just begun a $150,000 fundraising campaign for overdue structural improvements. But in other aspects of the operation, Lakewood has retained its old-theater charm.

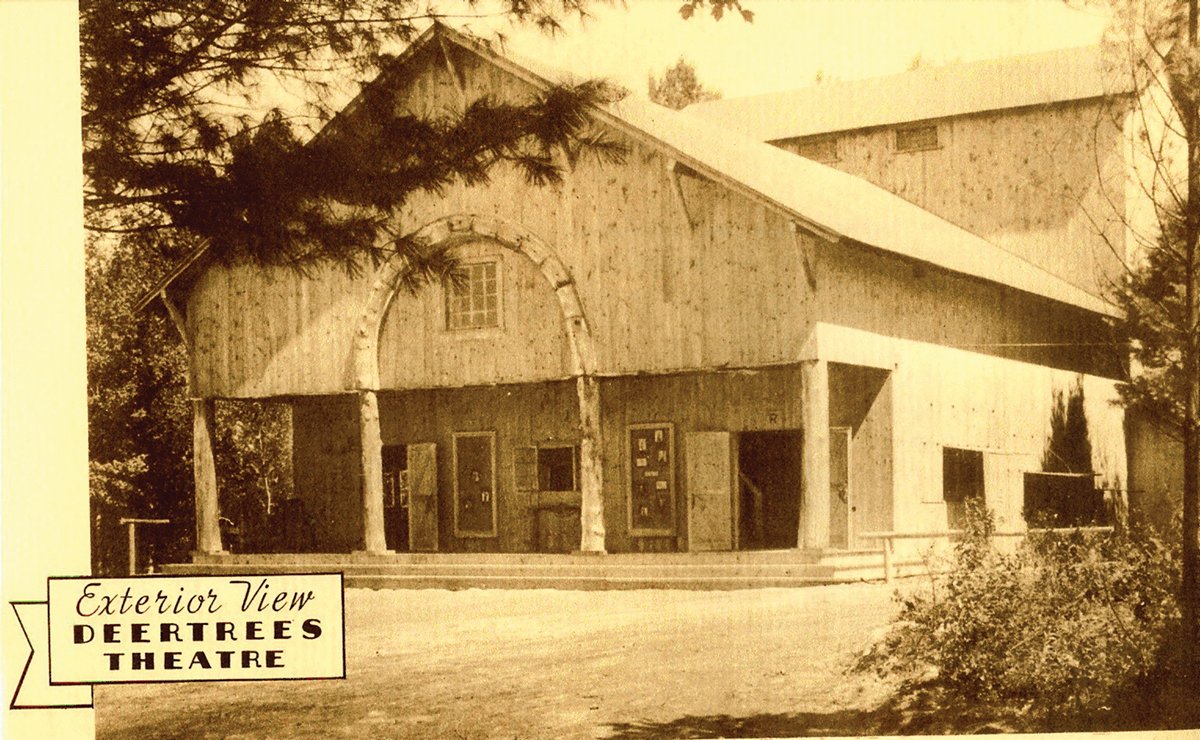

“We are trying to preserve as much of it as we can,” Irwin said. “We still have people who climb in the rigging and pull on ropes to make it all work.” Nowhere in Maine is the character of an old theater better maintained than at Deertrees Theatre in Harrison in western Maine. It was built in 1936 as an opera house, and designed by a man known for making great theaters. Harrison G. Wiseman designed Deertrees as “the most technically perfect theatre possible.”

He made it with hemlock in the Adirondack style, and within its early years, it was considered as nice a theater as any on Broadway, but without heat or much in the way of amenities. The charm was in the location.

Built with large, screened windows, Deertrees allows the outside world into the theater. At night, theater-goers can hear the sounds of the summer rain splashing on the ground, tree branches rustling in the wind and the chirp of insects.

Deertrees Theatre in Harrison, is among the oldest theaters in the state. Photo: Courtesy of Deertrees Theater

The newly formed Deertrees New Repertory Company, under the direction of Portland Stage production manager Andrew Harris, has a three-season show planned for this summer. The theater has struggled in recent years, and Harris is putting together a season and long-term plan to help the theater thrive in the 21st century. As part of its 80th anniversary in 2016, Deertrees is hoping to raise $80,000 for improvements to the building and grounds. As alluring as the old hemlock is, it requires a lot of maintenance, Harris said. “We want to improve the facility, but not change it,” he said.

That’s the challenge of summer theater—finding ways to keep it alluring and self-sustaining economically while also retaining the character and history of the old buildings.

In Monmouth, part of the allure is Shakespeare. The rest is Cumston Hall. The Theater at Monmouth is Maine’s official Shakespearean theater, and this summer Producing Artistic Director Dawn McAndrews has programmed two Bard plays, “The Winter’s Tale” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” among other offerings.

Monmouth produces its plays at Cumston Hall, a beautiful building with stained-glass windows and a large tower that nearly reaches above the trees. Built in 1900 to serve as hub for the town with an opera house, library and municipal offices, Cumston Hall is among Maine’s finest architectural gems.

No one knows the challenge of balancing history while running a business better than Guptill at Hackmatack in Berwick. He lives in a house on the theater grounds, just as generations of Guptills before him have. Hackmatack is personal, he said. It is tied to his own history.

Guptills came to New England in the 1600s, and settled in Berwick soon after. Their farm was like any other small New England farm, with the barn its centerpiece. Steward of the land and interested in finding ways to use the farm in other ways, Gutpill began the theater company in 1972. He’s not interested in giving it up anytime soon, despite the challenges of change.

The old barn has too much going for it to not open it up to the public every summer, he said.

“People like coming here,” he said. “They say we’re one of the most charming theaters in all of New England.”

It’s all in the wood.

Bob writes about the arts in Maine for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram. In addition to visiting museums and galleries and attending plays, musicals and concerts, he enjoys watching and participating in sports. He lives in Berwick with his partner, Vicki.