Going the Way of the Wabanaki–by canoe

Four days on the Penobscot River offers a journey deep into the landscape and its native culture.

View of the Penobscot River from Sugar Island.

MAP COURTESY OF JAMES ERIC FRANCIS

By Saisie Moore

Photos by M. Dirk MacKnight

VIEWED FROM A GREAT DISTANCE, the Penobscot River watershed reaches like a lightning bolt across Maine, its East and West branches forking from headwaters north of Moosehead Lake down to the mouth of Penobscot Bay. From the banks of the Passadumkeag River, it’s a far more peaceful sight—a shining green current that slips endlessly between grassy islands and beneath silver maples.

Unsure of where the current would lead, I joined 10 other guests last August for a Way of the Wabanaki expedition with Mahoosuc Guides. Polly Mahoney, who founded Mahoosuc Guides with her partner Kevin Slater in 1990, would take us along a picturesque stretch of water and deep into the culture of the river’s namesake: the Penobscot Indian Nation, meaning “people of the white rocks.” The Penobscot River and the people have shared a long history that threads through the millennia like the watershed itself.

We meet at the Passadumkeag put-in (in the Algonquian language, “that place above the gravel bar”). Mahoney begins by etching a map into the soil with sticks and rock to show the 6-mile journey on which we’ll soon embark, our belongings bundled into dry bags. Next comes a lesson in paddle strokes. We learn how to pry, draw, sweep and J-stroke in the air with paddles that Slater crafted out of maple, ash and cherry.

Balancing out our clumsy efforts are four Penobscot river guides: Chris Sockalexis, Jason Pardilla, Ryan Kelley and Damon Galipeau. They share a wealth of stories, skills and meals with us over the next few days. Besides guiding, they also play important roles in their community, acting as a tribal archaeologist, council member, woodworker and paddling champion, respectively.

The Mahoosuc and Penobscot guides first met during a 2014 canoe tour organized by Maine Woods Discovery to celebrate the 150-year anniversary of the publication of The Maine Woods, Henry David Thoreau’s reverential account of his backwoods explorations. The crew recreated the last leg of the legendary river trip taken by Thoreau and Joe Polis, navigating Penobscot territory from Moosehead Lake to Indian Island (“the wettest 18 days I’ve ever seen,” Pardilla recalls). Since then, the crew has collaborated to create the Way of the Wabanaki canoe trip to introduce visitors to the ancestral lands and culture of the Penobscot Nation.

Penobscot guide Chris Sockalexis explains the construction and history of the wigwam.

A natural fishing weir, the Passadumpkeag’s downstream course requires nimble navigation through boulder fields and shallow washes. The guides appear to know every rock and section of quick water as they lead our fleet of eight boats downriver as it ribbons among islands. “The tribe owns all these islands,” Sockalexis points out from the stern of my boat at one of many wooded knolls in the channel. “There are 52 in total, all the way from Medway to Old Town.”

We land on a grassy bank just upstream of Oloman Island, a quarry site for the revered red ochre, and eat a picnic lunch surrounded by Joe Pye weed and goldenrod. As we eat, the first of many bald eagles we will see on our journey spirals overhead and lands in a tree on the opposite shore. After a couple more hours of paddling, we land on the shore of Sugar Island, our base for the next four days. The expedition is largely family-friendly and inclusive of all skill levels—our group’s members ranged in age from 11 to over 60, each with different paddling experience. The downstream trajectory of the trip, coupled with paddling support from multiple guides, means the half-day paddles are never too physically strenuous.

A Penobscot summer retreat for generations, Sugar Island was named after the sweet serviceberries or “shadbush” that once grew here. Networks of trails, created with Herculean effort by Kelley early last spring, span the eastern side of the island and run a perimeter trail around its exterior to converge at the traditional gathering spot on the southern shore. All eight cabins have been restored since their construction in the 1970s and are now comfortably fitted with screen doors and cots. While accommodations are more elevated than tent camping, guests should be comfortable with outhouses and river bathing. Sockalexis and Pardilla recall childhood summers spent at camp among friends and family—the remnants of a high ropes course at the island’s center speak to their former hijinks.

A guest admires the interior of the wigwam.

We wander toward an eastern clearing, past the “Lunch Ledge” swimming spot, to see a traditional Wabanaki wigwam constructed from black spruce boughs and birch bark that gleams gold in the light. Sockalexis describes the daily life of a Penobscot family as we examine the structure. During the pre-contact era predating the establishment of permanent European communities in the 16th century, the wigwam’s roughly eight-foot radius would have accommodated an entire family and their daily traditional routines. Sockalexis points out the hatch in the roof where smoke from the fire would exit and the textured bark interior walls that would be lined with animal pelts come winter.

Upon our return to camp, preparations are underway for the first of many delicious and decadent meals seemingly pulled from thin air. Days begin and end with a campfire crackling beneath huge cast-iron pans of sautéing vegetables, filled with another of Mahoney’s feasts. “They say food is the thing people remember best about a trip,” she says, tossing walnuts over garden-grown kale. The communal effort and enjoyment of the food give the experience a nostalgic, summer-camp quality.

As we settle around the fire, Sockalexis, the tribe’s archaeologist, tells us that the Penobscot people have been here for around 13,000 years. He’s spent the last several years consulting on the development of Katahdin Woods and Waters, a national monument lying in Penobscot ancestral lands, which once spanned the Kennebec, St. Croix and St. John watersheds across Maine and beyond. “Now our lands cover less than 1% of Maine,” he says. The Wabanaki Confederation of Penobscot, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy and Mi’kmaq tribes is one of the few tribal nations never to have lost their native lands to settlers. However, through a long process of occupation and political maneuvering, settlers reneged on agreements and denied tribal land claims, whittling the Penobscot Nation’s territory down to a fraction of its former size. Many of the members of the current Penobscot Nation, which numbers around 2,400, live on Indian Island just across from Old Town, once an important Penobscot tribal village.

Over the course of our three-night stay on Sugar Island, our group is given an immersive look into the Penobscot Nation’s ancestral ties to this land and the turbulent story of their survival following European settlement. Over a traditional meal of salmon and foraged fiddleheads, Penobscot tribal historian James Francis, encourages our curiosity and humble ignorance in a session he calls “Anything you’ve ever wanted to ask an American Indian.” A skilled orator, he takes us on a sweeping journey through Penobscot history.

Like Francis, each of the guides share what they know and have experienced as native tribal members. Our discussions are free-flowing and open, covering spirituality and language, persecution and prejudice—and dive into the politics of elver fishing, too. Even the youngest guests listen raptly to the stories.

Penobscot guide Jason Pardilla demonstrates how to pitch seal a birch bark canoe.

Each new day brings new experiences shared by guests and guides. The trip’s only overcast morning is lit up by the arrival of a traditional Penobscot birch bark canoe. An object of rare beauty, the canoe is constructed from birch panels bound to ash gunwales with black spruce roots, with a bow and stern made from carved cedar. Pardilla demonstrates how to seal the seams of the birch panels with sticky spruce pitch heated over the campfire. The building process takes upward of 400 hours to complete, though gathering the materials can take more than a year. Every detail is a masterclass in patience, ingenuity and craftsmanship, from sourcing huge pieces of birch bark to etching intricate designs. Pardilla began his canoe-building education as a teenager; decades later, he’s still a self-described apprentice of the art. After each guest steps into the boat, we are swept across the water in a flash by Damon’s expert paddle strokes. In Mahoney’s words, the sensation is “like riding a feather on the water.”

One island afternoon, the group takes a journey back in time with Sockalexis, a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, for an exploration of Maine’s geological history, traveling “15,000 years in about 20 minutes.” The time-bending talk culminates in a demonstration of traditional flint knapping that renders a flaked flint arrowhead.

After one evening meal, we’re startled by a sudden voice and drumbeats soaring through the trees. A nationally recognized performer and visual artist, Firefly the Hybrid, appears unannounced to lead us in a handful of traditional songs. The Penobscot self-described hyper-creative is a headline act at the annual Santa Fe Indian Market, and we’re treated to a private audience with his extraordinary talent. “Nothing else sounds like singing on our Native lands,” he says. The songs carry from his chest and hit us in ours.

Dancing around the campfire with Firefly the Hybrid singing and drumming.

Two idyllic afternoons are spent under the gentle leadership of Jennifer Neptune, director of the Penobscot Nation Museum, herbalist and renowned basket maker. A steward of cultural artifacts, she has fought to see objects long held in external archives and collections—like baskets, tools and beadwork—returned to the tribe. “We believe these objects have a spirit; a purpose in this life,” she says. “They can still communicate, inform and educate.” She guides us through the process of weaving bookmarks from sweetgrass and black ash—the latter a culturally important resource among Northeastern tribes. Neptune describes the looming threat of destruction from the invasive emerald ash borer that has laid waste to ash groves across the country and is now approaching her ancestral lands. The chance to work with the precious and finely grained wood is a vanishingly rare privilege.

As we begin our clumsy crafting, we fall into deep state of absorption interrupted with laughter, all ages leveled to a childlike state of focus and fellowship. The final effect, no matter our skill level, is fragrant with sweetgrass, a scent somewhere between almonds, cinnamon and hay.

The next day, Neptune leads us on a tour of the island and reveals the plant communities we’d so far overlooked. “We refer to each plant as a ‘who’ not a ‘what’,” she tells us, demonstrating the respectful and reciprocal relationship the indigenous communities share with their nonhuman neighbors. We meet groundnut, sarsaparilla and blue vervain and taste wintergreen and Indian cucumber.

Hours of deep cultural immersion and paddling are interspersed with long mealtimes, walks around the sun-dappled trails, an exhilarating river float, and stretches relaxing around the campfire. We spend two full days on the island and two days paddling on either side of it. On a city break, that same amount of time can pass in an exhausting blur. On Sugar Island, it’s a luxurious time spent rising and sleeping with the sun and watching the light shift across the campsite.

For these four days, I forget to look at a phone or mirror. Cut adrift from routines and modern stresses, looking through the lens of tribal history, I have time to refocus: the river’s constant, gentle flow sets a pace worth following.

Canoe trip outfitters abound across Maine’s waterways, but few offer you the privilege of connecting so intimately with the indigenous cultures that have shared an epic history of connection, reciprocity and survival with the rivers you paddle on.

For more information, visit: www.mahoosuc.com and www.penobscotnation.org

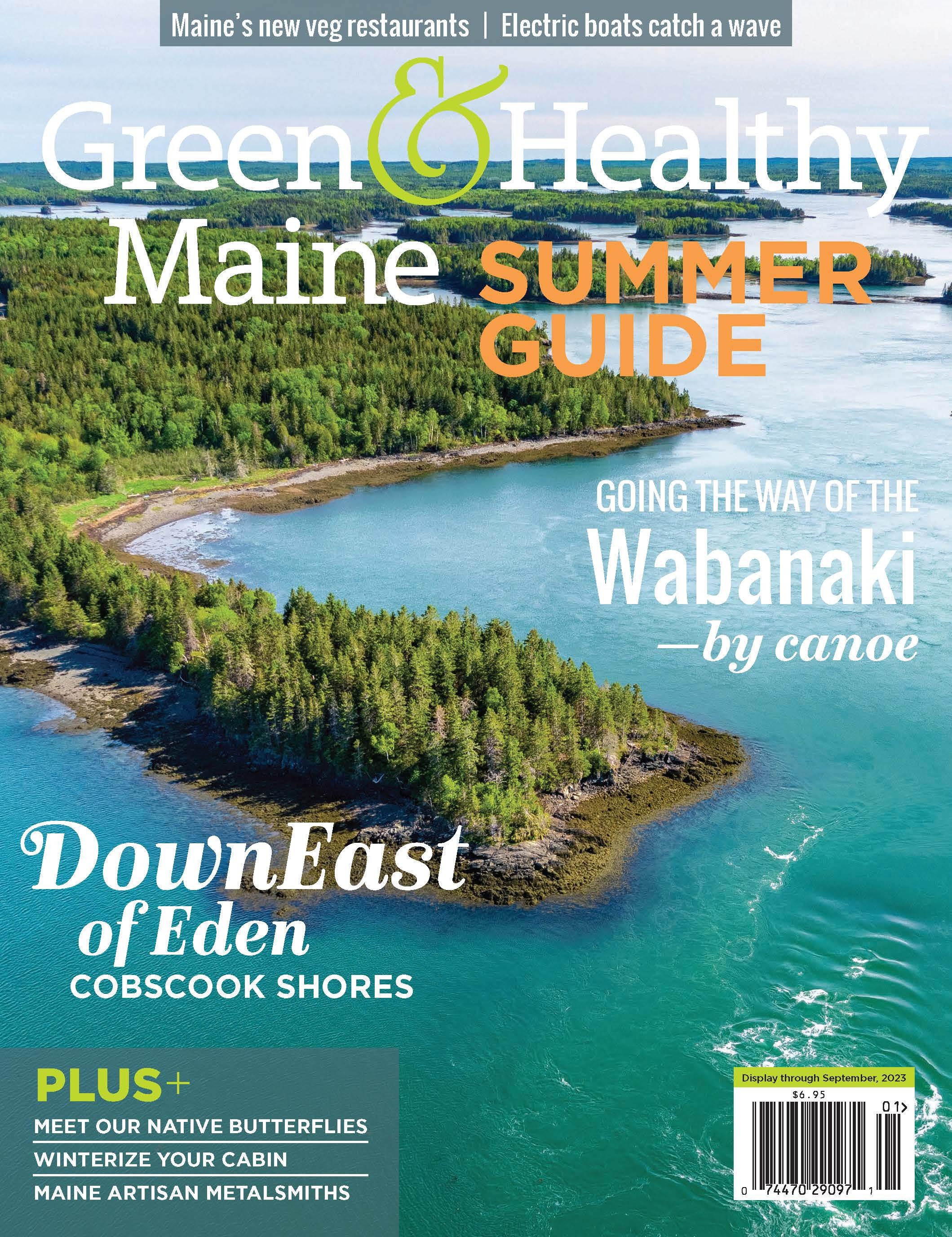

On the cover: In far DownEast Maine, the parklands of Cobscook Shores protect miles of pristine shorefront.